What did Harold Pinter write about Shakespeare?

Browse the newest Faber titles, from debut novels and gripping crime thrillers to the best new poetry, children's books and refreshed editions of classic works of literature.

View AllWhether you're looking for a gift or to treat yourself, find special editions, letterpress prints, Faber branded merchandise and much more here.

View Allfeatured

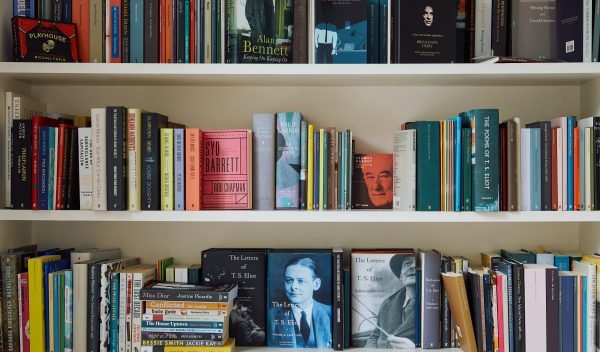

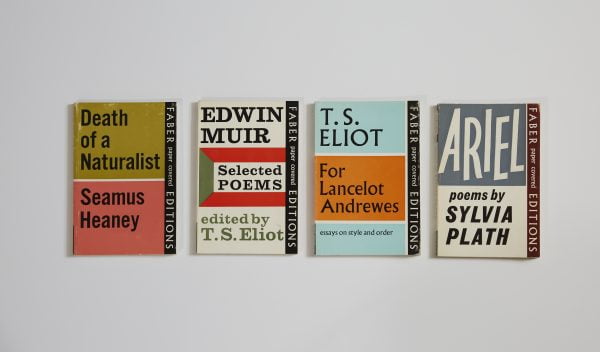

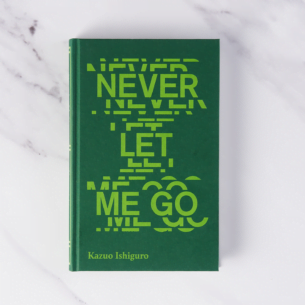

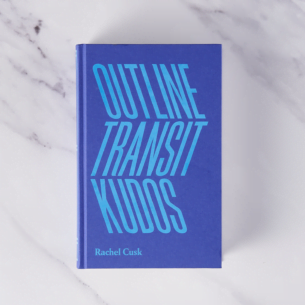

Home to William Golding, Sylvia Plath, Kazuo Ishiguro, Sally Rooney, Tsitsi Dangarembga, Max Porter, Ingrid Persaud, Anna Burns and Rachel Cusk, among many others, Faber is proud to publish some of the greatest novelists from the early twentieth century to today.

View Allfeatured

Our non-fiction catalogue features thinkers, writers and entertainers – from the QI team and Lenny Henry to James Shapiro and Jenny Uglow – whose books stimulate joy and laughter or new ways of thinking about the world.

View allFor nearly a century Faber has published the best poetry in the world. Explore all our poetry here.

View AllFrom Nobel Laureates Samuel Beckett and Harold Pinter to theatre greats Tom Stoppard and Alan Bennett to rising stars Polly Stenham and Florian Zeller, Faber Drama presents the very best theatre has to offer.

View AllFaber is proud to collaborate with writers and actors to produce audiobooks that bring classic novels and contemporary bestsellers to life in sound. Browse our fast-growing list of titles.

View AllRead, watch and listen to the latest news, interviews, reading lists and quizzes from Faber authors, staff and our community of readers and writers.

View All In Journal

Read about the Faber story, find out about our unique partnerships, and learn more about our publishing heritage and present-day activity.

Learn More

Faber & Faber was founded nearly a century ago, in 1929. Read about our long publishing history in a decade-by-decade account.

Learn MoreFind out about careers at Faber, manuscript and poetry submissions, and how to apply for copyright permissions

Learn MoreAs a publisher, we believe in our collective power to help deliver tangible change towards a more equal and fair society, through our publishing, campaigning, outreach and advocacy.

Learn More- Why Join Faber Members

- Member Events

- Members Only Shop

- Exclusive Articles

- Sign in to your Membership

Faber Members have access to live and online events, special editions and book promotions, and articles and quizzes through our weekly e-newsletter.

Learn More

See Faber authors in conversation and hear readings from their work at Faber Members events, literary festivals and at book shops across the UK.

View EventsFaber Members have exclusive access to special and limited editions from some of our most famous authors.

View All

Enjoy exclusive interviews, films, reading lists and quizzes as a Faber Member. Simply sign in to your account to unlock all articles or sign up for free.

View Exclusive Articles

Access your Member profile to track your orders, view saved items and update your details.

My Membership- BOOKS & SHOP

- AUTHORS

- EVENTS

- JOURNAL

- ABOUT US

- FABER ACADEMY

- FABER MEMBERS

- New In

- Gifts & Exclusives

- Fiction

- Non-fiction

- Poetry

- Drama

- Children's

- Audio

- Our Story

- Our History

- Work With Us

- Social Responsibility