Bake Off with Gordon Burn

By Lee Brackstone

Gordon Burn is not a hard person to talk about, or make sense of, in the world we find ourselves in nine years after his death. He comes up often in my engagement on social media; a ghostly afterlife that may have fascinated someone who was so engaged with how the media warps and distorts reality through the lens of celebrity. Now, in a world infected by social media – which was only just taking off when Gordon died in 2009 – we are all celebrities. Everyone is famous, not for fifteen minutes but five seconds: the length it takes to read a tweet and digest the anger, vanity and loaded irony that often characterises the form. Seen in the context of ‘the news as a novel’ – Gordon’s famous subtitle for his last book and arguably his masterpiece, Born Yesterday – Twitter feels like the projection of a dream he may have had some time back in the early millennium.

So, I was on the Tube thinking about Gordon and the six years of this prize – which has done so much great work to keep his legacy alive – and his impact as a writer, which of course goes through subtle changes as we approach a decade since he left us. I picked up a copy of Metro and read the headline: ‘Serial Killer Rose West Wins Prison Bake Off with Victoria Sponge Cake’. There was that familiar sound again: the Gordon Burn claxon. Has there ever been a more Gordon Burn headline than that? Now I don’t particularly want to talk about Gordon’s time on Cromwell Street and his descent into the unthinkable in his book, Happy Like Murderers. I worked on that book in my early twenties and remember Gordon laughing at me in the pub on a first encounter when I told him reading his book in progress was giving me nightmares. I have no doubt I was trying to impress him. I soon learned it would take more than that. Years later, I was reminded of this encounter when I read the artist René Magritte’s response to his incredulous art dealer on unveiling his surrealist masterpiece, Personal Values, in 1952: ‘A picture which is really alive should make the spectator feel ill’.

What struck me about the Rose West–Bake Off headline was the horror that we have perhaps at last reached peak Gordon Burn, when Britain’s most notorious serial killer is celebrated for her baking skills. Gordon intuitively understood the relevance of reality TV shows as soon as they hit the screens fifteen years ago. He realised this was the celebrity endgame playing itself out. And the Big Brother House has now, predictably, played out its own entropy. These things last a generation, and then they mutate. Jade Goody, who some of you will remember, was a reality TV star who thought ‘East Angula’ was another country outside the UK. I remember Gordon, again over a pint, cryptically telling me he was going to write a book about Jade Goody. He loved Jade Goody. I think he saw her innocence, her vulnerability, where others saw stupidity and vulgarity. Gordon was never mocking or cheap in his assessment of art, popular culture and celebrity, whether seen through the form of a novel, non-fiction or journalism.

What struck me about the Rose West–Bake Off headline was the horror that we have perhaps at last reached peak Gordon Burn, when Britain’s most notorious serial killer is celebrated for her baking skills. Gordon intuitively understood the relevance of reality TV shows as soon as they hit the screens fifteen years ago. He realised this was the celebrity endgame playing itself out. And the Big Brother House has now, predictably, played out its own entropy. These things last a generation, and then they mutate. Jade Goody, who some of you will remember, was a reality TV star who thought ‘East Angula’ was another country outside the UK. I remember Gordon, again over a pint, cryptically telling me he was going to write a book about Jade Goody. He loved Jade Goody. I think he saw her innocence, her vulnerability, where others saw stupidity and vulgarity. Gordon was never mocking or cheap in his assessment of art, popular culture and celebrity, whether seen through the form of a novel, non-fiction or journalism.

Sure enough, he saw the horror, the fatigue and the dysfunctionality first, but this always led him to a place of compassion and, nearly always, humour. ‘There are some very violent women on the wing and a lot of them are very aggressive towards West because of her crimes,’ said Metro of the aforementioned Rose. ‘But she tends to defuse situations by offering other prisoners cakes and biscuits.’ Even a serial killer can make a nice Victoria sponge. Just as even the nation’s Fairy Godfather, Jimmy Savile – the subject of a previous winner of this prize, Dan Davies – can be a paedophile.

There is no doubt in my mind that Gordon Burn was a great writer, one of the defining writers of the late twentieth century and our own fin de siècle. The word ‘great’ is bandied about a lot, as is the word ‘visionary’. The truth is that very few writers are visionaries, with the obvious exception of William Blake. We like to think writers are visionaries because this reassures us about the often-uncomfortable place we have ended up. Great writers have the gift of reading the runes that culture presents to us, and this gives us the illusion they are somehow prophets. We gravitate to these writers for answers and expect too much wisdom, just as we go to our musicians for epiphanies. The fact is, the most relevant writers, and those whose influence seems to be absorbed through osmosis into the culture after they have stopped writing, or died, have left a trail of breadcrumbs, clues, questions that help us define this moment. Gordon’s books, whether they be about footballers, pop stars or politicians, leave us with more questions than answers. And this is the mark of truly great art – like looking at a Rothko in a gallery or misunderstanding a Magritte – that it is enough to be in the presence of the mystery; that plot, denouement and moral certainty are overrated.

Great writers leave a footprint. But we discover, years after they are gone, that most of them were walking in snow. Very few seem to grow with significance, the mark of authenticity, as the culture catches up with their writing in the afterlife. I can imagine Gordon reading that headline about Rose West and the Victoria sponge cake. And he would perhaps see things in that headline we wouldn’t yet understand. And he might even decide to write a novel about it.

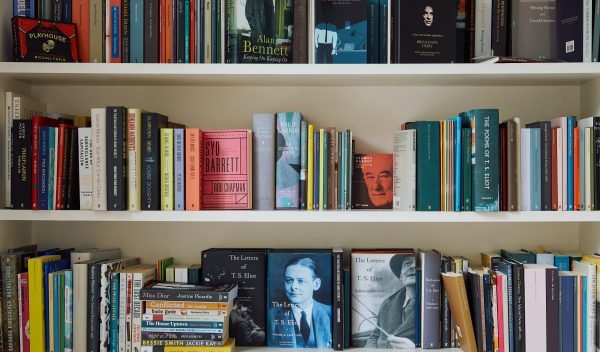

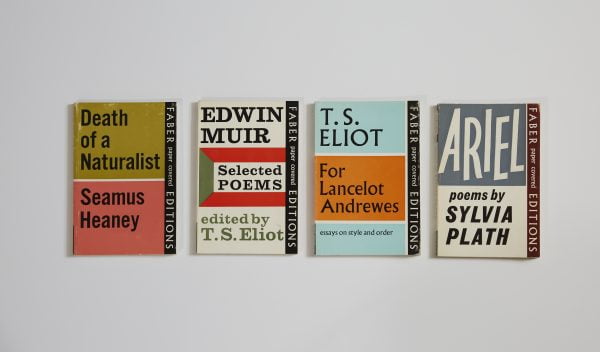

Lee Brackstone is an editor at Faber and Creative Director of Faber Social

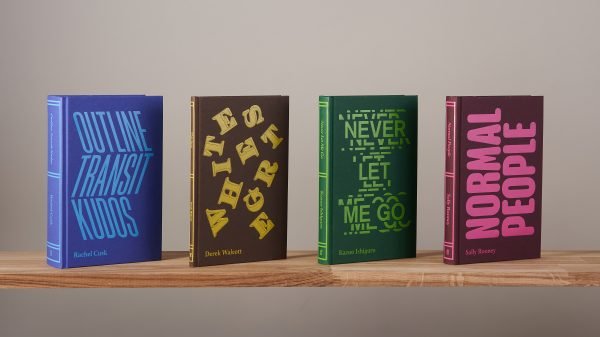

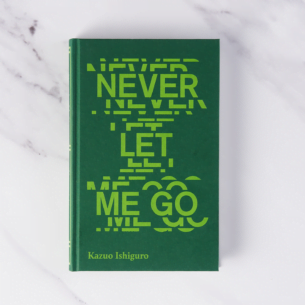

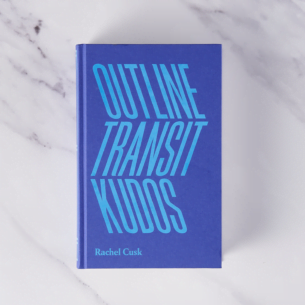

The Gordon Burn Prize seeks to reward a published title – fiction or non-fiction – which represents the spirit and sensibility of Gordon’s literary methods. We love novels which dare to enter history and to interrogate the past and non-fiction brave enough to recast characters and historical events to create a new and vivid reality.

The 2018 Gordon Burn Prize was awarded to Jesse Ball for Census.