Benjamin Myers’s Foreword to The Spire

William Golding was a visionary.

In literature they don’t come along frequently. Once or twice in a generation if we’re lucky – more often than not they’re barely recognised in their lifetime.

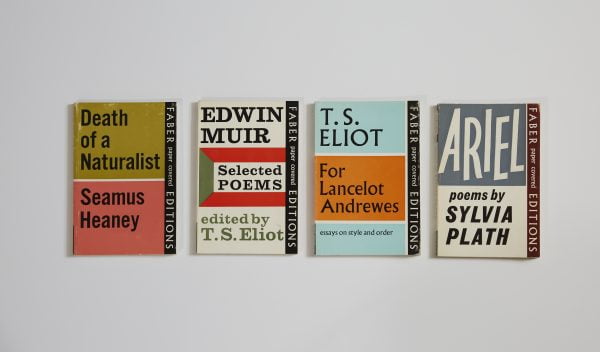

Golding is an exception, for although he achieved huge commercial success with his first novel, Lord of the Flies, his subsequent works inevitably sat in its shadows. Few remember the second time a climber summits the tallest mountain, yet he was at least acknowledged – most notably with the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1983 and a knighthood in 1988 – because Golding wrote better novels, and The Spire is his masterwork.

Within it is a self-contained world, one confined by solid stone and blind pride, and it is a novel whose themes, I’d wager, will still be recognisable to readers in five hundred years’ time. Perhaps it takes a visionary to recognise another, and in his opening trilogy of novels – as strong a body of work as any in twentieth-century literature – Golding created several characters with what we might call ‘second sight’: there’s epileptic Simon, who represents the soul of man in Lord of the Flies (1954), Lok, the Neanderthal who reconstructs memories as pictures in The Inheritors (1955) and the purgatorial mental unravelling of the titular Pincher Martin (1956). All see beyond the parameters of their existence; all are transcendent.

It’s a flawed visionary whose troubled mind we occupy in The Spire – that of Jocelin, Dean of an unnamed cathedral that was inspired by Salisbury, adjacent to which Golding worked as a teacher for sixteen years in Bishop Wordsworth’s School, ensconced in Cathedral Close. The simple plot is perfect for an elevator pitch: pious cleric believes God has chosen him to erect a huge spire. Yet beneath this simple framework is a deeper well of big questions concerning faith, folly and desperate desire; for Golding, a simple story was never enough. The tragedy of the human condition was his career-spanning speciality.

The creation of the novel was no less challenging a task than that given to – or rather pressed upon – the architects and masons by Dean Jocelin, despite their continued protestations at the impracticality of it all. It was written during a tumultuous period for Golding, as he attempted to juggle his growing success, raise young children, oversee house renovations and undertake extensive lecture tours of the US. He was a writer neither at ease with writing, nor the attendant scrutiny that fame brought with it. He rarely gave interviews, despised discussing his latest work and frequently submitted his novels to his longstanding editor, Charles Monteith, at Faber & Faber with a pessimistic note, presumably a tactic deployed to pre-empt any forthcoming criticism.

The Spire had a particularly difficult gestation. The idea for ‘a funny story’, which would be partly historical and partly set in contemporary times, came about in mid-1961. During a US lecture in December 1961, he mentioned plans for a novel that would ‘explore a symbol’ – that of the cathedral in the fictional town of Barchester.

Golding lightened the load on himself somewhat by doing almost no research whatsoever – a rarity, one might assume, for a novel set in the Middle Ages. When later quizzed about this by critic Frank Kermode during a stroll around Salisbury Cathedral, Golding replied, ‘Oh, I just came here and said to myself, “If I were to build a spire, how would I go about it?”’

On 28 February 1962, Golding wrote to Monteith to say that ‘after shilly-shallying and mucking about, I got down to the book and wrote it (between fifty and sixty thousand words) in a fortnight and am now properly flaked out’, before joking – we think – that it was to be called An Erection at Barchester.

Despite the endless prevarication, distraction and a missed deadline, the fact that Golding drafted The Spire in a matter of days is staggering given the moral and theological complexity at play here, and yet it was a punishing creative endeavour entirely in keeping with the spirit of the novel itself. It went through several torturous drafts, until Golding officially submitted what he called ‘this ghastly book’ in May 1963, upon which he promptly travelled straight to Cannes Film Festival for the premiere of the adaptation of Lord of the Flies, whose huge sales were now bringing in an income so considerable that Golding complained he didn’t know what to do with it all: the ultimate burden of the successful debut author.

The context and mechanics of the creation of The Spire are important, for such visionary work comes at a cost to the writer who must pay a psychic price for the readers’ benefit alone. Here Golding’s struggle can be felt in the challenges for those inveigled into building the spire atop the cathedral. Life imitating art imitating life, and so it goes.

Yet Dean Jocelin struggles less than his minions, for in him we see that weakness that has lain within the most fervent, God-struck believers throughout the ages: certainty of faith. He, like so many before and after, believes himself to be chosen by God and as the spire rises, octagon by octagon, shrinking all beneath it as it grows to a height of four hundred feet, the Dean’s faith is unwavering. Despite warnings that the original foundations of the structure are nowhere near deep enough to support the added mass of stone – and that, in fact, the building is essentially floating upon a raft of mud and brushwood – Jocelin pushes forward, because so pure and godly are his intentions that the practicalities of physics and reason have no place here.

It’s hardly a plot spoiler to note that the reader can predict impending bathetic downfall from the outset. Master builder Roger Mason can see it, as can dissenting Father Anselm, and the army of labourers too: ‘There comes a point,’ remarks Mason, ‘when vision’s no more than a child playing let’s pretend.’

Sure enough, fissures in Jocelin’s character become gaping cracks as he struggles with both a gnawing back pain, which he interprets as the presence of a guiding angel, and his desire for flame-haired Goody Pangall, wife of the cathedral’s errant servant, captured in the erotically charged glimpses of a true voyeur: ‘Her hand clutched the pillar behind her, hiphigh, and her belly shone about the slit of her navel through the handtorn gap in her dress.’

This is Golding at his best. And all the while the foundation pit becomes a malevolent force, a seething portal to a hellish chthonic underworld, at odds with the heavenly realm that Jocelin surely believes will await him.

The Spire is loaded with similar such powerful imagery, most notably the spire itself. It doesn’t take a Freudian reading of the book to see that it is a growing phallic symbol that teeters over a moiling mess of adultery, impotence, guilt, desire, pride and sexual agency. Golding’s biographer John Carey writes that ‘the ruthless willpower with which Jocelin drives on the spire’s “erection” is, it is suggested, a sublimation of his lust as well as – or rather than – an expression of pure faith.’

Upon publication, The Spire greatly divided critical reception, with wildly different reviews running in most major publications. E. M. Forster wrote an encouraging letter, remarking that its great literary merit was ‘the sense of weight – stone weight’, and it is this literary density that has allowed the book to bed in to the soil of modern English literature. Almost all things good and evil begin with man’s folly. Pride, moral struggle and monumental acts of hubris are at the core of all engineering spectacles, religious movements, wars and the rise and fall of empires, and there is no better novel that demonstrates this.

In which case the point bears repeating: William Golding was a visionary.

There is little doubt that The Spire is a work of great importance.

It is a vision.

Succumb to a churchman’s apocalyptic vision in this prophetic tale by the radical Nobel Laureate and author of Lord of the Flies, introduced by Benjamin Myers.