Elise Valmorbida: My Suitcase Stories

To kick off the blog tour for The Madonna of the Mountains – a richly evocative tale of love and survival in the Veneto region and recent pick for The Times Book of the Month – here’s an exclusive photo journal from the book’s author, Elise Valmorbida.

The seed of The Madonna of the Mountains was planted long ago and far away. Growing up Italian in Australia meant growing up with migrant stories. My head was full of people and places that seemed foreign and yet were utterly familiar—part of me, like my Italian face and my Italian surname. In recent decades, I’ve been gathering notes about Italy: random personal observations on anything from language to landscape. Sometimes I’d sit with my aunt in her kitchen, scribbling into a notebook as she recounted wartime experiences. She’d be sipping coffee, or stewing artichokes, or showing me how to make gnocchi (unwritten recipes, no measures, everything done by habit and handful). At a certain moment, she’d wipe her hands on her apron, and go off to find me an old photo, perhaps a memento.

The seed of The Madonna of the Mountains was planted long ago and far away. Growing up Italian in Australia meant growing up with migrant stories. My head was full of people and places that seemed foreign and yet were utterly familiar—part of me, like my Italian face and my Italian surname. In recent decades, I’ve been gathering notes about Italy: random personal observations on anything from language to landscape. Sometimes I’d sit with my aunt in her kitchen, scribbling into a notebook as she recounted wartime experiences. She’d be sipping coffee, or stewing artichokes, or showing me how to make gnocchi (unwritten recipes, no measures, everything done by habit and handful). At a certain moment, she’d wipe her hands on her apron, and go off to find me an old photo, perhaps a memento.

There were other storytellers, not just family and extended family. Old friends. Neighbours. The strangers I’d meet at a sagra celebrating the local mushroom or cheese, huge crowds seated in vineyards, eating and drinking, talking late into the night. I took notes about anything and everything—courting, conscription, flouting a Fascist, when to plant in the moon’s cycle—not with a specific project in mind, but because I didn’t want to forget this richly fascinating, disappearing world. And people liked telling me things, knowing that someone was genuinely interested and that they would not be forgotten. It was like a haphazard oral history project.

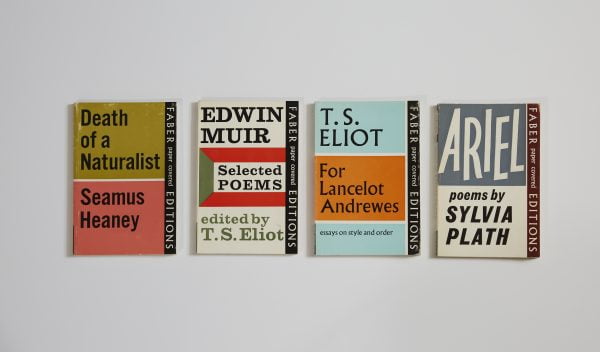

Ordinary letters—by ordinary people—gave me some insight into the language and concerns of my characters in early 20th-century rural Veneto. The voice of the Madonna of the Mountain is rooted in a very specific place and culture. I made her up, but she could look a little like one of these santini holy cards I’ve collected from ecclesiastical shops and holy sites.

I decided to make The Christian Bride the only book that my novel’s protagonist Maria Vittoria would possess. Written in very churchy Italian, and published in 1911, this tiny leather-bound volume is brimming with religious advice, prayers and rituals “for my dear young girl”.

There are family hand-me-downs… There are museums… And there is eBay, a vast research resource, visual, verbal, unpredictable, real. Some of the militaria and other wartime artefacts that appear in my novel are: a WW1 brass cartridge with a saint inside, a cloth badge made in Dachau, and a sculpture of Mussolini’s head with his profile spun into 360 degrees, all-seeing.

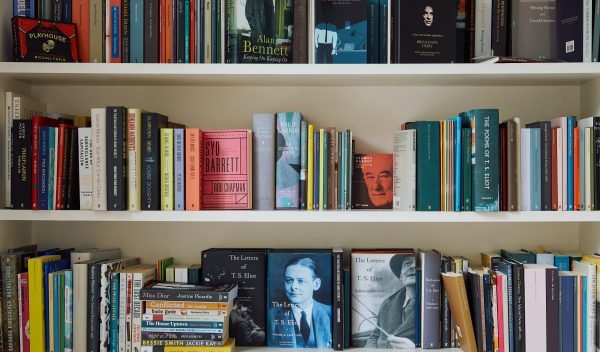

Once my novel was underway, I became more disciplined about research, reading countless books, in English and in Italian. I referred again and again to a technical-historical dictionary of Vicenza’s territory and dialect, La Sapienza dei Nostri Padri. Cinema was inspiring too. Literally, neorealist films such as Paisan, Bicycle Thieves, or Rome, Open City. And laterally: I love Le Quattro Volte for its patient, attentive, near-documentary gaze. I wanted that sort of intensity as I described my characters doing the washing or slaughtering a pig.

In Italy I explored historic sites and places that are nowhere on a map. I visited churches and museums. I foraged for facts—and edible wild things. I scoured the internet there too; local searches yielded local special-interest sites I couldn’t find in the UK. Ditches are an important part of the Veneto landscape. Fosso, the fictional town Maria moves to, means ditch. It’s just the kind of name a real place would have.

Emblems associated with Mussolini’s rule were defaced or destroyed after World War II, but this one in the Roman ghetto remains intact. The building is the Theatrum Marcelli, which was conceived by Julius Caesar, and built by Augustus Caesar. It was a spectacular ruin in medieval times, when it was developed into residential property by the son of a Jew who changed his name, converted to Christianity and founded the powerful Pierleoni family. In 1929, Mussolini’s men buttressed the buildings with bricks, and added the Roman fasces with the year: A VII E F (Year Seven of the Fascist Era). My book’s chapter titles are numbered in this way.

The northernmost corner of the Veneto borders Austria, and you know that song Edelweiss… In Italian, the flower is a stella alpina, or alpine star. In the novel, Maria Vittoria thinks: “The stella alpina tucked inside her Christian Bride book stayed intact, and the gentian flowers kept their blue for years. Perhaps she will have a long life too, because she’s from the mountains and made of strong stuff.”

“Se lavora par magnare e se magna par lavorar. One works in order to eat, and eats in order to work.” Food is a recurring theme in the novel. Gathering, growing, harvesting, cooking, preserving, salvaging… Food in Autarchy, food as rationed allowances with coupons, food as torture, food as hunger, food as survival, food as love. Maria would tell you (as I do!) that foraged stinging nettles make for a delicious pasta sauce, soup or omelette.