Did you, in your youth, experience a particular revelation that writing literature was to be your chosen path or was the progress gradual?

There was no such revelation. I grew up among practical people, mostly farmers, who were often great storytellers and creative problem-solvers, but would never have used the terms ‘writer’ or ‘artist.’ It didn’t cross my mind that people like me could write books. I only loved to read them, and did so continuously, absorbing literature as a quiet education running alongside my regular schooling (I liked science). I kept a journal and wrote poems and stories that I didn’t plan to show anybody, ever. It wasn’t until my late twenties, after I’d read great works by the likes of Wendell Berry and Bobbie Ann Mason (both rural people from my part of the country), that I began to take my own writing a little more seriously. But it still felt pretentious to call myself ‘a writer,’ so I didn’t, until after I’d published my first novel at age thirty-two.

Are you ever curious to revisit characters from earlier novels (it would be great to see what Turtle is up to now), or does the lure of pastures new always take precedence?

It’s a cocktail-hour game at my house to throw characters from my earlier novels together in new situations: What if Eddie Bondo from Prodigal Summer went on safari in Africa, stayed in the hotel run by Rachel from The Poisonwood Bible and they had a torrid fling?

Don’t hold your breath; I won’t be writing that scene. What keeps me at my writing desk is the challenge of something I’ve never done before. Back in my schooldays I was that kid who wanted to major in everything; I love diving into the research for each book, learning about new places, professions and conundrums. I structure each novel with a craft challenge that’s new to me – a story set in two different centuries (Unsheltered), a narrator who avoids first-person pronouns (The Lacuna) a narrator with dementia who comes temporally unglued (Animal Dreams). This ratchets up the terror factor. If I’m seriously afraid I won’t be able to pull it off this time, I know I’m working at the edge of my powers. I thrive on that adrenaline.

‘‘Don’t hold your breath; I won’t be writing that scene. What keeps me at my writing desk is the challenge of something I’ve never done before.’’

What kind of bird would you like to be?

Funny you should ask. I decided years ago that if I could elect to be a non-human animal, I’d be a raven. You get flight with that option, obviously, but even among birds, ravens stand out for their joie de vivre. Humans have assigned them a reputation for creepiness (the official name for a flock is ‘a conspiracy of ravens’), but that’s probably grounded in jealousy. When I see a gang of them chortling and hopping around together, yes, I know they’re laughing. But it’s not about me. These birds are canny and adept and know what’s important in life. They do somersaults and barrel rolls in the air, for the pure fun of it. Yep, I’m envious.

You are my favourite writer, tackling big themes by telling stories about often small lives. How do you balance the personal and the epic sweep of the political?

Thank you. I owe everything to my readers, and consider my own act of creation to be only half-finished when I send off a book to be published. The other half happens when a reader absorbs it. Having said that, I’ll confess that I write without thinking very much about what anybody wants from me. I’ve written about child abuse, colonial arrogance, climate change, the fatal flaws of capitalism, um, death by snakebite – you don’t get a backlist like this by trying to be marketable.

The truth is, I never start a novel with the so-called ‘epic sweep’ in mind. I begin with a question that’s bugging me. I pose it to myself on a human scale, in terms of behavior and psyche, because that’s the terrain of literature. For example, to begin Flight Behavior I did not open a file and write ‘Climate Change’ at the top. I started with a curiosity about something I see happening in my neighborhood, among farmers I know: Why is it so hard to talk about climate change, or believe in it, even while it’s ravaging our crops and lives? To answer that, I listened. I considered the stakes and where people were getting information, and how humans, in general, decide what we believe. I researched the psychological literature and found surprises. (Hint: We all generally decide what we believe first, then look for supporting evidence.) I invented characters with complex histories and a situation that would dramatize their decision-making processes. Threw in local color, conflict, a miraculous vision, some sexual intrigue, and voila! That, plus some years of careful attention to every single sentence, makes a novel.

‘‘I invented characters with complex histories and a situation that would dramatize their decision-making processes. Threw in local color, conflict, a miraculous vision, some sexual intrigue, and voila! That, plus some years of careful attention to every single sentence, makes a novel.’’

Has lockdown affected your writing at all, and if so, how?

Like all families in the world, mine is socked with grief and worry these days. We’re stretching ourselves to keep everybody safe, from my nonagenarian father to my newborn grandson. But that wasn’t your question. My work is full-speed ahead. When I get to retreat to my office, it’s a paradoxical escape to leave my personal worries behind and shoulder the human condition at large. Since the start of this pandemic I’ve knocked out half a draft of a new novel.

Writers only succeed if we love being alone for a lot of our waking hours, year after year. We’re professional introverts. ‘Social distancing’ is my natural state. I live on a farm, in a steep mountain valley that we Appalachians call a ‘holler.’ All I need is here in reach: a garden’s bounty, an entertaining family, friends who drop by, a huge little world of beauty and grace. In earlier times, my husband always made a joke of counting how many days it had been ‘since Barbara left the holler.’ Now, instead of a hermit, I get to call myself a good citizen.

Name three living writers who you greatly admire.

Wendell Berry, Alice Munro, Marilynne Robinson.

What made you decide to release a book of poetry at this time?

I’ve always loved poetry. It was the first form I undertook seriously as a writer, with some early publications. But then I wrote my first novel and got an advance check of sufficient size that I could quit my day job and write another novel. Wow! Just like that, fiction became my way of supporting my family. I don’t think anybody since Rumi has made a living by writing poems; poets also have to teach and give readings. (Come to think of it, so did Rumi.) So I’m delighted to stay home and be a novelist, with poetry relegated to a more private passion.

But in recent years, as I watched my country and the world becoming unhinged, I’ve turned to poets for strength and solace. I begin and end most days with friends like Pablo Neruda, Emily Dickinson and Mary Oliver, to name just a few. They arouse my brain and quiet me down, both at the same time, dissolving partisan barriers to remind me of the things we all feel together: joy, grief, wonder. Poetry started taking me over, not just as a reader but as a writer, and it struck me that a book of poetry might be just the thing to launch into perilous, alienating times. My editors agreed. (This was a year ago – little did we know!) I’m still a bit startled that this happened: my secret passion turned out into the light of day. But I’m glad. Poetry deserves its place in the sun.

Where is your favourite writing spot?

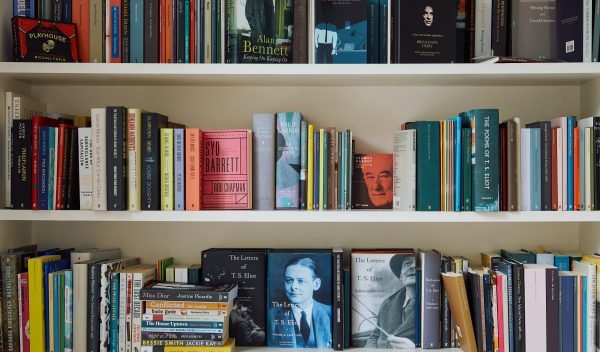

My desk, in my office, upstairs in our farmhouse. I’m there now. Behind me is a wall of books, in front of me a wall of windows looking out onto a forest. At this moment a heavy rain is bending the boughs of the poplars. And I’m standing, not sitting. When I write, I tend to go into an immobilized trance (basically forgetting I have a body) for hours at a time. And then, ouch. The human body wasn’t designed for sitting like that. So, my husband bought me a standing-up desk, and I love it. Occasionally my feet fall asleep, but I haven’t fallen over yet.

‘‘At this moment a heavy rain is bending the boughs of the poplars. And I’m standing, not sitting. When I write, I tend to go into an immobilized trance (basically forgetting I have a body) for hours at a time.’’

Is there a big difference between writing prose and writing poetry?

A poem and a novel both require imagination and concentrated devotion, but the processes feel nothing alike. I’d liken it to the difference between a fabulous first date and a marriage.

How did you choose a title for your book of poetry How to Fly (in Ten Thousand Easy Lessons)? (Vanessa, Liverpool)

With novels, I usually have a title in mind from the beginning that serves as a lodestar for the whole writing process. This was different. With so many titles to choose from within the collection, I printed out the table of contents and polled anybody who could be persuaded to care. This is America, remember, so we arrived at no consensus. The marketing departments won out in the end, and I think their choice was perfect. All these poems address the project of becoming whole, grounded and also weightless in our lives, and how that process never really ends.

But I also favored ‘Forests of Antarctica,’ for reasons I can’t explain. ‘Six Women Swimming Naked in the Ocean’ got a few votes, but probably would have attracted the wrong crowd.

How do you know when a poem is finished?

It’s finished when the deadline arrives. I love revision and believe that’s where most good art really happens. I could keep working on a manuscript forever if I didn’t have someone gently reminding me that we need to go to press. I might still be revising my first novel but I had a hard deadline on that one – I wrote it while I was pregnant with my first child. Right before she was born, I went into a mad frenzy of housecleaning and realized I would have to throw away that big, messy pile of pages, unless I could make myself write ‘THE END’ and mail it off to an agent. Took a deep breath, did it.

‘‘I might still be revising my first novel but I had a hard deadline on that one – I wrote it while I was pregnant with my first child. Right before she was born, I went into a mad frenzy of housecleaning and realized I would have to throw away that big, messy pile of pages, unless I could make myself write ‘THE END’ and mail it off to an agent. Took a deep breath, did it.’’

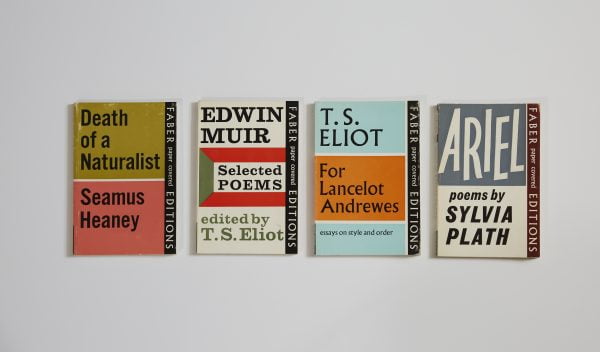

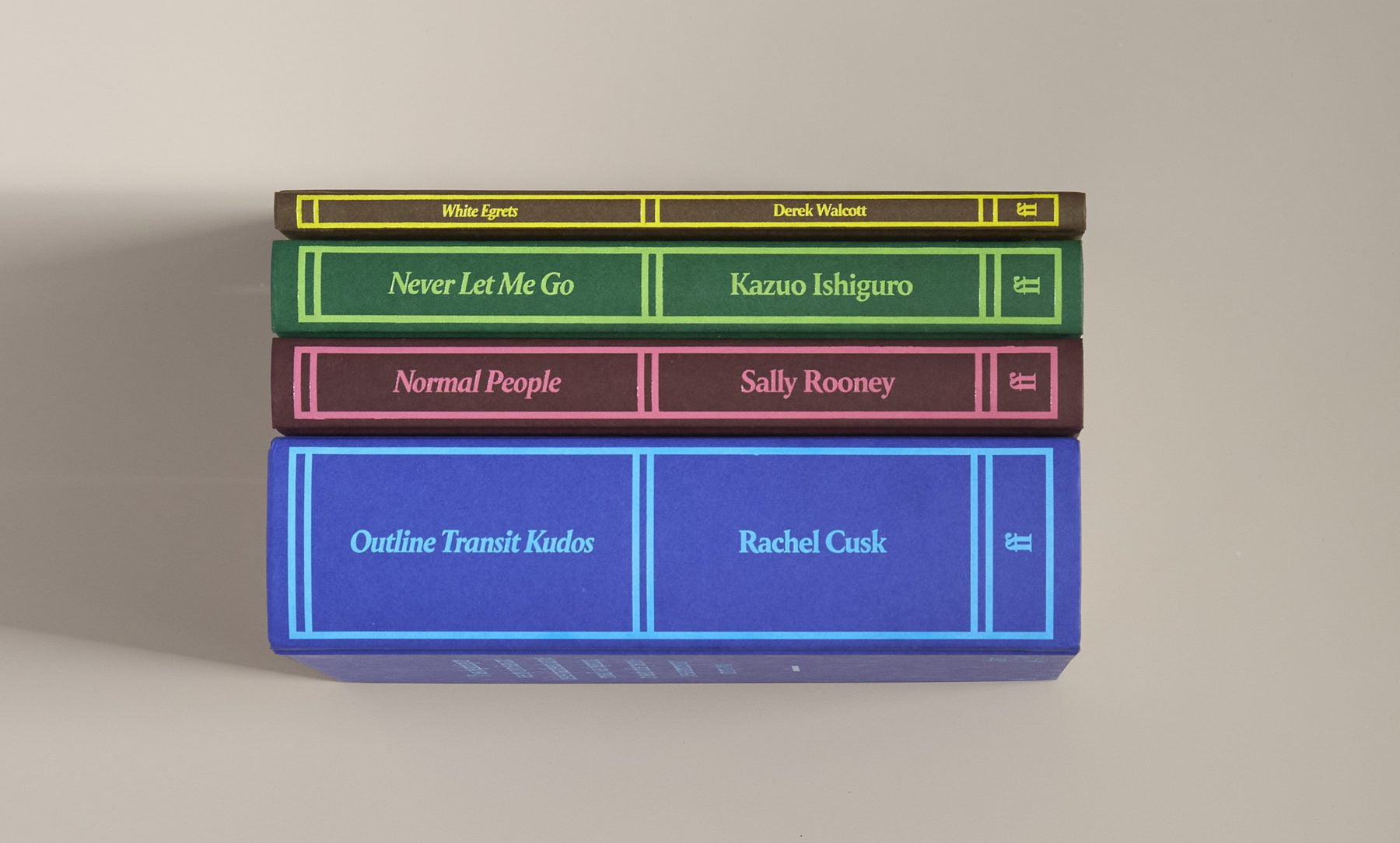

Become a Faber Member for free and join a community that brings together great novelists, poets, playwrights, thinkers, musicians and artists with readers in the UK and around the world. Faber Members have access to live and online events, special editions and book promotions, and articles and quizzes through our weekly e-newsletter.