Poetry for a Change: National Poetry Day 2018

For National Poetry Day 2018, we asked some Faber poets and staff for their poetic recommendations around this year’s theme Poetry for a Change.

Rachael Allen, poet

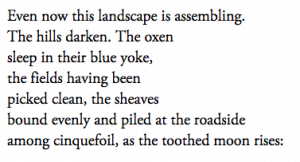

All Hallows by Louise Glück is one of my favourite poems. It feels to me both implicitly and explicitly to be dealing with change (as lots of poems do) in that it envisions a physical landscape of fields at harvest – a seasonal time of change – while creating an internal sense of anticipation. The idea of change is foregrounded from the first line, the ‘Even now’ creating a kind of unstable, rolling moment, wherein a landscape is always ‘assembling’. Among the many ingenious things this poem does, it reminds me that change is not something that happens periodically but a constant state of being, that change is what we live in.

– from The First Four Books of Poems by Louise Glück (The Ecco Press, 1995)

Lavinia Singer, Assistant Editor, Poetry

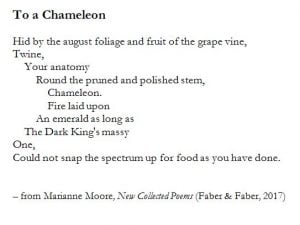

Here are two poems that describe wondrous transformation in nature.

Marianne Moore’s poems were themselves forever changing, reshaped and revised over the poet’s lifetime, as illuminated in the recent New Collected Poems edited by Heather Cass White (Faber & Faber, 2017).

The Old English riddles of the Exeter Book are ingenious examples of the genre, and require a total shift in the reader’s approach, to imagine what lives behind the cunning phrases.

Mary Jean Chan, poet

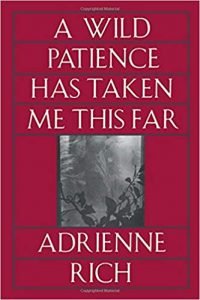

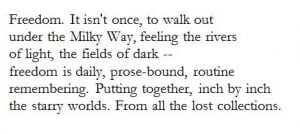

Adrienne Rich’s poetry has always seemed to me to be about change – in the sense of Rainer Maria Rilke’s dictum ‘you must change your life’ – but also gesturing at the need for broader social change in order to liberate all those who have been historically oppressed across societies and cultures. In these politically tumultuous times, I keep coming back to Rich’s words for inspiration and solace.

– from ‘For Memory’, A Wild Patience Has Taken Me This Far by Adrienne Rich (W. W. Norton & Company, 1981)

Hannah Marshall, Marketing Manager

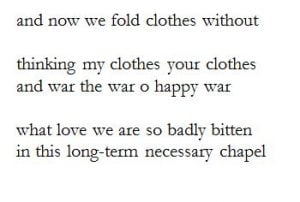

Life, by its nature, is rarely a constant thing and it’s only natural that we tend to focus on the more momentous changes that occur – deaths, births, marriages, the meeting of a significant other. Often though it’s the slower, more subtle changes that we find hard to recognise or capture and that’s why I love Jack Underwood‘s poem, ‘War the War’, which is, in Jack’s words, ‘a love poem for people who have been together a long time’. I think it does a remarkable job of expressing the often gradual shift from that all-consuming, passionate new love to a more familiar, domesticated, yet tender, established love.

– from ‘War the War’ by Jack Underwood

Richard Scott, poet

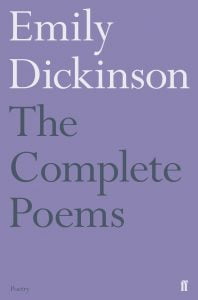

Could there be a more evocative rendering of change in poetry than the speaker’s transformation in Emily Dickinson’s ‘My Life had stood – a Loaded Gun’; in just twenty four short-ish lines the loaded gun acquires a ‘Vesuvian face’ and fires, raining down – what? Poetry, violence, faith? There has been so much discussion and important scholarship about this poem that it can be hard to decide what Dickinson is actually writing about, indeed the poem is a kind of riddle. For instance who is the gun – perhaps a woman denied agency or a person without faith or a poet without a muse? And who is the Master – possibly the object of desire from Dickinson’s erotic Master letters or a publisher or perhaps even a deity? For me, the poem has always had an intense queer tinge – when I think of the loaded gun I also think of a queer person on the cusp of coming out, being able to express their sexuality and all the contrasting violence and love that might ensue. Indeed what little we know of Emily Dickinson’s sexuality does not rule this reading out; and her symbols, the phallic gun and the terse Master, could surely exist in a landscape of same-sex love. Parts of the world have changed somewhat since Dickinson’s Amherst, a place of vile and near-constant subjugation, intoxicating religious fervour, impending civil war and an unhealthy preoccupation with abduction narratives, but the resonances of this poem are clear: Dickinson saw us all as loaded guns, awaiting the right trigger finger, the right target. Dickinson believed in the possibility of seismic personal change.

Could there be a more evocative rendering of change in poetry than the speaker’s transformation in Emily Dickinson’s ‘My Life had stood – a Loaded Gun’; in just twenty four short-ish lines the loaded gun acquires a ‘Vesuvian face’ and fires, raining down – what? Poetry, violence, faith? There has been so much discussion and important scholarship about this poem that it can be hard to decide what Dickinson is actually writing about, indeed the poem is a kind of riddle. For instance who is the gun – perhaps a woman denied agency or a person without faith or a poet without a muse? And who is the Master – possibly the object of desire from Dickinson’s erotic Master letters or a publisher or perhaps even a deity? For me, the poem has always had an intense queer tinge – when I think of the loaded gun I also think of a queer person on the cusp of coming out, being able to express their sexuality and all the contrasting violence and love that might ensue. Indeed what little we know of Emily Dickinson’s sexuality does not rule this reading out; and her symbols, the phallic gun and the terse Master, could surely exist in a landscape of same-sex love. Parts of the world have changed somewhat since Dickinson’s Amherst, a place of vile and near-constant subjugation, intoxicating religious fervour, impending civil war and an unhealthy preoccupation with abduction narratives, but the resonances of this poem are clear: Dickinson saw us all as loaded guns, awaiting the right trigger finger, the right target. Dickinson believed in the possibility of seismic personal change.

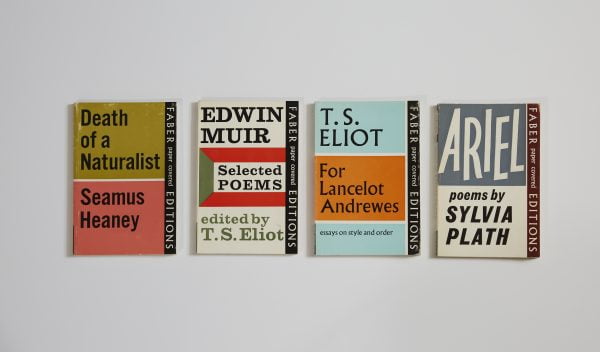

– from The Poems of Emily Dickinson, Edited by R. W. Franklin (Faber & Faber, 2016)

Joanna Lee, Communications Administrator

Ishion Hutchinson, poet

‘They also serve who only stand and wait.’

That is the beautiful last line of Milton’s ‘When I Consider How My Light is Spent’. Those three strong words: ‘serve’, ‘stand’, and ‘wait’ are three distinct actions, indistinguishable from moral courage. The genius of the line, partly, is how the words linking them enact the actions of serving, standing, and waiting. Nothing is insignificant, every bit is necessary. I think the line speaks to changes which are subtle and to the ordinary sublime which is anything but ordinary. They who? Wait and serve also.

Namra Amir, Trainee Publishing Assistant

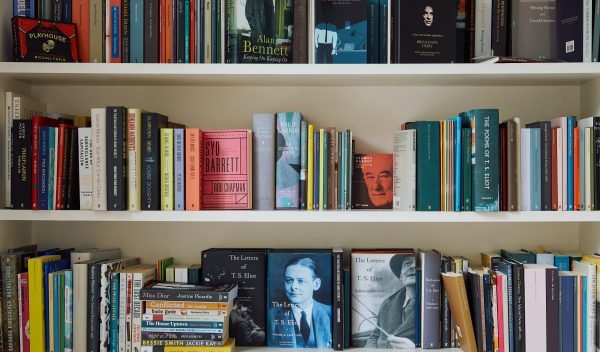

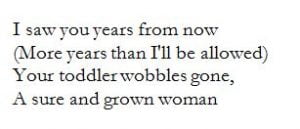

Growing up and learning Irish poetry, everyone knew or learnt about Seamus Heaney. ‘Blackberry Picking’ and ‘Digging’ were the first Heaney poems I discovered and I fell in love with his writing. So when he passed away, I went to visit Seamus Heaney’s Home Place. I read the poem ‘In Time’ and the line ‘More years than I’ll be allowed’ really struck a chord because I was reading the last poem he ever wrote. It made me think about the passing of time, and how I was no longer in school learning a new Heaney poem. Now, I’m older and reliving my childhood memories through his poetry.

– from Seamus Heaney’s ‘In Time’, in 100 Poems (Faber & Faber, 2018)