Nicola Upson on Cyril Hare’s An English Murder

The snow did not start to fall in earnest until after darkness had set in, but once begun it continued with ever-increasing density until well after daybreak.

Sentences like this, taken from Cyril Hare’s 1951 novel An English Murder, have a peculiar charm at this time of year. As a flood of reissued Christmas detective stories testifies, there’s something about the combination of sherry, fruit cake and sudden death that never fails to appeal – so much so that even the most discerning of crime readers will happily turn a snow-blind eye to deficiencies of plot or originality if the victim is dressed as Santa Claus and the arsenic is hidden in the pudding.

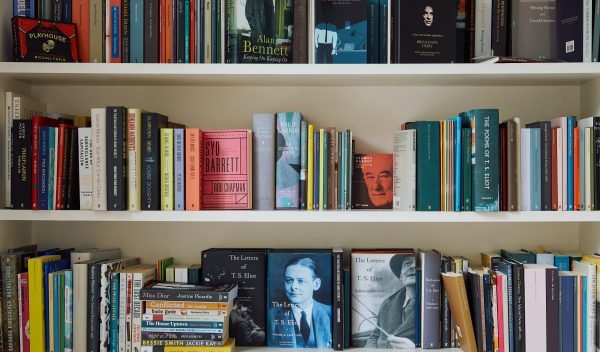

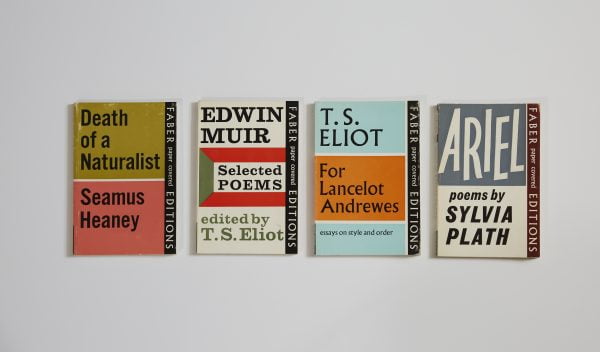

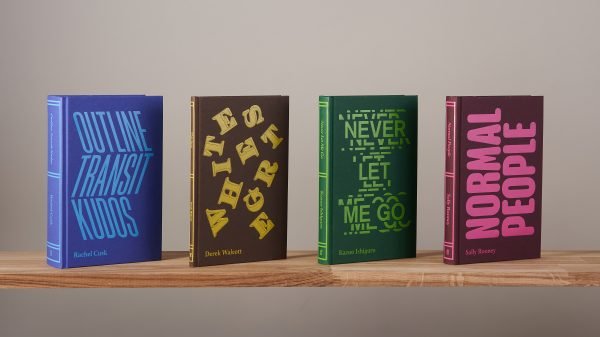

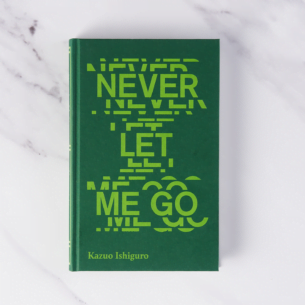

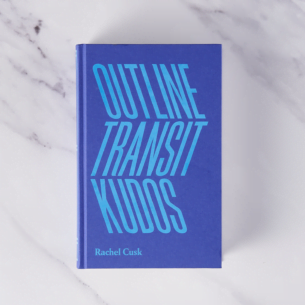

No such allowances need to be made for Hare’s festive offering, though. An English Murder, fittingly celebrated in a handsome new Faber edition, is a classy and entertaining country-house murder – a Christie-esque whodunit which stands as a consummate example of how to respect tradition while extending its boundaries. Cyril Hare was the pseudonym of Alfred Alexander Gordon Clark (1900–1958), a judge who took his pen name from his London home, Cyril Mansions in Battersea, and his chambers in Hare Court, and who set his detective novels firmly within the classic traditions of the legal thriller. He was called to the bar in 1924, practising in both civil and criminal courts before working as legal assistant in the Public Prosecutions Department during the Second World War, and for the last eight years of his life he served as a county court judge in Surrey. His career gave him a uniquely informed perspective on crime and justice which he transferred effortlessly to his fiction, blending it with a subtle sense of comedy and an instinct for the dramatic. Critically applauded during his lifetime, his work has also been championed by modern writers, most notably P. D. James, who succeeded him on the Faber crime list – but elegant prose, a dry wit and rich settings transformed by personal experience give these two great writers much more in common than their publisher.

Hare was the creator of two memorable series characters: the Scotland Yard detective Inspector Mallett; and the ageing lawyer Francis Pettigrew. An English Murder is unusual in that it features neither, leaving an eccentric group of amateurs to fend for itself when two murders occur in rapid succession in a snow-bound country house. At first glance, the characters might be the predictable stereotypes of the genre – respectable politician, deferential butler, scorned lover and foreign outsider – but Hare breathes glorious life into them all, second-guessing the reader’s expectations and transforming his cast into flawed, believable people with what Tatler perceptively called his ‘muffled compassion for human nature’.

The novel generally recognised as Hare’s masterpiece is Tragedy at Law, but An English Murder rivals it for popularity. In the build-up of atmosphere and suspense, the sense of foreboding which settles like frost on the window panes, and the multi-layered conversations which reveal both character and clues, the author is at the top of his game. Without doubt, it’s a novel of its time. Warbeck Hall exists in a world where shoe horns are readily found, butlers have no interest in politics, and an atmosphere of male dominance scents the air as tangibly as woodsmoke or whisky; ‘The room seemed to be suddenly full of women,’ writes Hare at one point, as he might describe wasps or flies or anything else that swarms – unbidden and unwelcome – to disrupt the natural order of things. And yet what really distinguishes this book from its contemporaries is an awareness that its time is all but over. Justice might prevail according to the conventions of the genre, but when the solution is revealed and the culprit identified, the post-war shifts in class and society which threaten the foundations that the Hall – and the detective novel – are built on will still be there. And as a dying Lord Warbeck stares out across his parkland, transformed temporarily by the misleading beauty of the snow, he is all too aware that the thaw of change is on its way:

All trace of the neglect and disrepair of recent times had vanished. The drive again ran smooth and straight between its avenue of pollarded limes. The bowling-green for once displayed a surface as flat and true as it had done when it had been the whole duty of an able-bodied man to keep it in order. It was an illusion, of course. Two days of thaw would suffice to reveal the hummocks and holes and weeds of reality – to reveal also, he thought grimly, half a dozen burst pipes at different points in the cumbersome old house which he would somehow have to find the money to repair. No matter. For a prematurely aged, sick man, it was pleasant to indulge in the illusion while it lasted.

And so it is for us. The classic Christmas detective novel might, like the snow, be a temporary, artificial distraction from the problems and injustices of everyday life, but it’s an enjoyable one – and for that reason we will go on loving it.

Nicola Upson

An English Murder is out now (£8.99), available here. Nicola Upson’s latest novel Nine Lessons (£12.99) is available here.