The Pulp Fiction behind Muscle

Alan Trotter discusses which books and films inspired his debut novel Muscle.

More than a decade ago I started writing a novel without planning, which is something I would recommend only provided you have a decade to spend writing a novel. To begin with I wrote maybe two pages, which involved a man without a name (he was, and remains in the finished book, just ‘_____’) being thrown out of a car and landing at the feet of another man, called Box, and the two of them agreeing to work together, hiring themselves out as purveyors of violence, as muscle. The narrative voice obviously, immediately came from hardboiled detective fiction, which was strange only because I had never read much hardboiled detective fiction, and yet there it was, clattering inside my head.

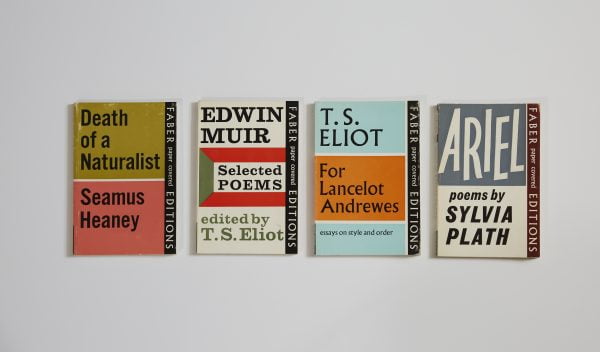

But of course everyone is familiar with the affectations and world-weary cynicism of the hardboiled detective (it’s a voice a little prone to lyricism and a little to quips, like a particularly self-pleased drunk), familiar with it even if they’ve never read a page of Dashiell Hammett or Raymond Chandler, because it has dispersed out into film and television, into adaptation, homage, pastiche, parody… I think my first experience with it was seeing Blade Runner when I was about ten-years-old (the original version, with Deckard’s voiceover), which installed it pretty deeply.

Anyway, it became clear the book that I was writing was about story-telling and about genre and also meant to use these things to talk about things like anxiety and guilt and determinism. It became clear that to be able to write it, I had to know more about the detective stories I was reassembling.

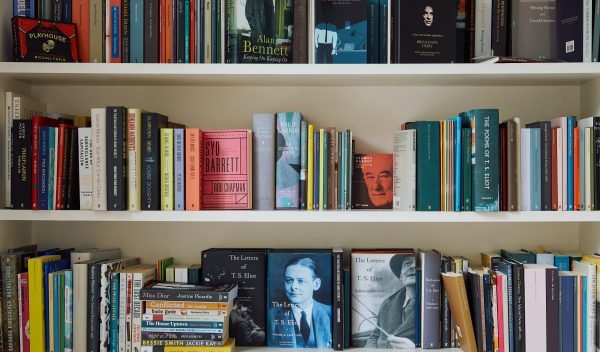

So I read books and watched films, lots of both. I made notes about plot, and notes about set-dressing and about language (frails, elbows, louses, gunsels, buttons), so I could make my (slightly off, un-placed, un-timed) counterfeit.

Some of the things I read and watched were very bad (though some of those were also very useful to the book), but some were extremely good, so here are a few quick recommendations from those years I spent in messy research, looking for art that would inform (or maybe just postpone) the writing of the novel.

Nightmare Town by Dashiell Hammett

Nightmare Town by Dashiell Hammett

While Chandler solidified the genre and put snap into the writing of the hardboiled detective, my heart really belongs to Hammett, who preceded him, and who created not just prototypical private eyes – Sam Spade and the Continental Op – but other varied and inventive delights. This collection is a good place to get a sense of his range and skill as a writer.

Rififi (1955), directed by Jules Dassin

Rififi (1955), directed by Jules Dassin

At the heart of this French film noir is the most compelling heist sequence ever made, and the vividness of every person in the gang – and the pathos of their unravelling – is indelible. Apparently Truffaut said “out of the worst crime novel I ever read, Jules Dassin has made the best crime film I’ve ever seen”.

Strangers on a Train by Patricia Highsmith

Strangers on a Train by Patricia Highsmith

Patricia Highsmith started her writing career in comics: she’d describe the work later as “like thinking up 3 grade-B or -C films every day”. The bare idea of Strangers of a Train is so colossally strong (two strangers meet, they each have someone they would like to see dead, they swap the murders) that even a mediocre crime writer would be able to retire on it. But Highsmith was a genius, so she darkly complicates it into a novel of unusual, unsettling intensity.