The View from My Window | Chris Pavone

No matter where you live, coronavirus has altered daily life. We’ve asked Faber authors to share a snapshot of their lives in lockdown.

On Friday 13 March we packed our suitcases with clothing and textbooks and novels and sports gear and computers and shelf-stable kitchen staples, loaded the car and fled Manhattan for our vacation home on Long Island, where we intend to live until this crisis abates, whatever that looks like.

The kitchen here is big enough for two people to cook at the same time (I’m savory, my wife sweet), with an island where we eat (and where our friends used to keep us company, with wine, while we cooked), plus a window bench to read and nap and play backgammon, and a built-in desk for household administration. A lot of life takes place in this kitchen.

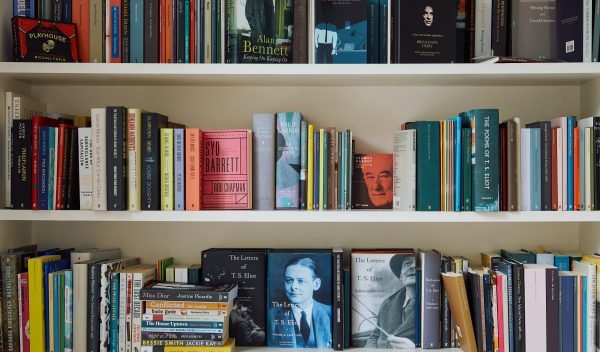

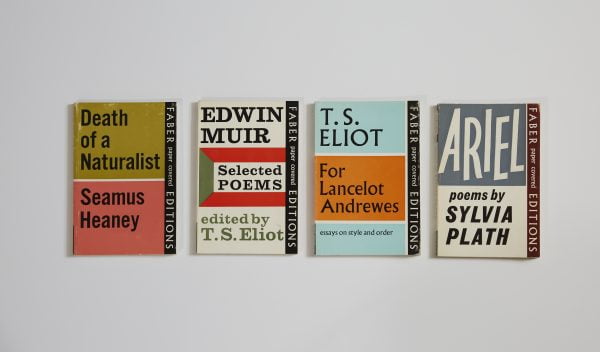

But I never imagined I’d live in this one room all day long, every day. My wife and kids have separate work spaces elsewhere in the house; not me. My built-in desk is in a corner, with a view of a majestic old cedar of Lebanon, which was transported here as a seedling from Lebanon a century ago by the foreign-service officer whose family owned this house for a few generations. I arrive to the kitchen at breakfast and rarely leave till after dinner clean-up. I write here, I read, I edit, I have Zoom calls, I alternate listening to horrifying news with soothing music, I let the dog in and out dozens of times, I do the crossword, I place massive online grocery orders.

And of course I cook. There’s almost always something on the burners or in the oven or both, I’m home-making duck confit and slow-roasting pork shoulders, pressure-cooking beans and stocks, long-simmering sauces and parboiling potatoes and brining chicken, and meanwhile Madeline has a sheet pan of focaccia rising and there’s sourdough starter bubbling and parchment-wrapped tea cakes and tins of cookies—

My god is it hard to not eat all day long. For a while it was also extremely hard to work: if the world is ending, what’s the point in writing a novel? On the other hand, if the world is not ending, I should be accomplishing something other than cassoulet.

We’re very fortunate in many ways, and during this pandemic we’ve faced no actual hardships, just adjustments, and fear. The city we fled from and the village we fled to are both virus epicenters with terrifying levels of infection and mortality. This is not something that’s happening somewhere else. I’m able to forget about this while I’m dicing onions, which is one of the main reasons I’m dicing so many onions. But sitting at my computer, facing a blank page and my own imagination, I often find it impossible to ignore what’s going on out there.

Chris Pavone’s latest novel, The Paris Diversion, is out now in paperback.